Protection money and limited rights:

The prehistory

Jews may have lived in Aquae Mattiacorum, ancient Wiesbaden, already in Roman times. The first Jew, named Kirsan, is mentioned in documents from 1385. Later, it was always only individual Jews who lived in Wiesbaden, unlike in Mainz, Worms and Speyer, where there had been flourishing Jewish communities since Roman times and throughout the Middle Ages. In 1427 there is a report of a Jew Gebhardt who owned a house near today’s Michelsberg. In 1518, the Jew Jakob from Nuremberg was mentioned in the records because he had to pay an annual protection fee. In 1570 a Jew named Moses lived in the Mühlgasse. At that time it was also known as “Judengasse”. The name was later transferred to the Metzgergasse, today’s Wagemannstrasse, where there was also a “Judenschule”. There was never a ghetto in Wiesbaden. The few Jewish families apparently lived among the other citizens, but with fewer rights. They were not allowed to own land, belong to a craftsmen’s guild, or perform military service. In 1638, the Jew Nathan received permission to settle in Wiesbaden for one year. At that time, the building of a large synagogue was still far away. Despite the small number of Jews, the Wiesbaden authorities repeatedly received complaints about the Jewish neighbors.

The synagogue building in 1869: a symbol of emancipation

The new synagogue on the Michelsberg was to become a piece of Jerusalem in the middle of Wiesbaden. The Jewish Community had chosen none other than the Nassau court architect Philipp Hoffmann (1806 — 1889) to build it. Hoffmann had already designed the Roman Catholic Bonifatiuskirche (1849) in the Luisenplatz and the Russian Church on the Neroberg (1855) in Wiesbaden. That he should now also build the synagogue was an expression of the religious tolerance and the generally prevailing liberal attitude in the mid-19th century, a consequence of the Enlightenment, and the French Revolution with its proclamation of human and civil rights.

Philipp Hoffmann designed the synagogue on the ground plan of a Byzantine central-plan building. In doing so, he alluded to the common roots of Judaism and Christianity. The building sequence of the new Wiesbaden houses of worship in the mid-19th century was a kind of Lessing’s ring parable set in stone, so to speak. All religions were to be treated equally. In 1864, the Anglican Church in the Kleine Wilhelmstraße had been completed. The daily contact with spa guests from Russia, England and the USA inevitably led to Wiesbaden’s cosmopolitanism. With the completion of the synagogue, anyone looking in the direction of the Michelsberg could see it: The Jews were now recognized citizens of the city. The almost fairy-tale-like large onion tower with its golden stars on an azure background and the Star of David on the dome was visible from afar. The synagogue had become a new landmark of Wiesbaden.

The old synagogue, built in 1826 in the Schwalbacher Strasse, soon showed signs of structural defects. Rabbi Benjamin Hochstädter was an early advocate for a new building, but the Jewish community did not go along.

Finally, it became too cramped due to the further influx of Jews. The community grew from 200 members in 1833 to 550 in 1863. As early as 1857, it had enough money to finance a new building. The Nassau building officials proved unwilling and delayed the building permit. But then Duke Adolph is said to have intervened and approved the “request” to build on a plot of land on the Michelsberg. In 1862, Philipp Hoffmann set to work. A year later he submitted the first plans, whereupon building permission was granted.

For the further development of Jewish architecture in Germany, Gottfried Semper (1803 — 1879) had set the trend with his synagogue in Dresden (1840). Semper built it in the so-called Moorish style, with round arches as a design element. Moorish was synonymous with oriental, and the Dome of the Rock was the topos for Jerusalem. The rock on which it stands, according to tradition, was the site of the burnt offering in the Jewish temple. On it, the forefather Abraham is said to have sacrificed a ram in place of his son Isaac. At any rate, Philipp Hoffmann built on the Michelsberg what the German educated bourgeoisie imagined to be a Solomonic temple. If Hoffmann had looked around St. Petersburg and Italy for the construction of the Russian Church, this time he traveled to Bad Cannstatt to be inspired by a villa that the architect Ludwig Zanth had built for King Wilhelm I of Württemberg.

He also inspected the new synagogue in Cologne (1861) by cathedral master-builder Ernst Friedrich. It had also been built in the Moorish style that had just become fashionable. The mourning hall at the Jewish cemetery on Platter Strasse (1891) was also built in this style.

In the case of the synagogue’s former building in the Schwalbacher Strasse, the Nassau state government had still stipulated that it should not be conspicuous in the townscape. “The singing of the Jews would then be less of a nuisance to passers-by than if the synagogue were in the ‘street line’,” wrote building inspector Karl Friedrich Faber, who planned the building. With this remark he probably represented the spirit of his time. When in 1826 the synagogue moved from its predecessor in the Obere Webergasse to the Schwalbacher Straße and they wanted to carry the Torah scroll into the new synagogue in a ceremonial procession, the State Ministry still brusquely rejected the request: “The Jews are not allowed any public rite at all, in that they do not enjoy the rights of a church, but are only tolerated in silence.”

Inauguration with the synagogue singing society: Royal visit to the Kurhaus

Things had changed now, in the late 1860s. On the afternoon of August 13, 1869, a large congregation, about 500 people, solemnly marched up the Schwalbacher Street to the Michelsberg with the Torah scrolls and songs of thanksgiving and praise, the school youth leading the way. They were followed by the bearers of the Torah scrolls and white-clad girls with the synagogue key. Among the participants were master-builder Philipp Hoffmann, led by the community’s board of directors and Rabbi Dr. Samuel Süßkind at its head, as well as clergymen of the various denominations, such as the Protestant Bishop Wilhelm Wilhelmi, and representatives of the civil and military authorities. The new synagogue had 500 seats. On the day of the consecration, however, it could not even remotely accommodate the audience. A huge crowd of spectators had lined up along the Schwalbacher Strasse and the Michelsberg.

“It was,” reported an eyewitness, “a solemn moment when, to the sounds of the organ, the oldest members of the congregation walked through the new magnificent temple with the Torah scrolls carried over from the old synagogue, when Rabbi Süsskind placed them in the sacred ark and lit the eternal lamp with the benediction.” Singing and organ playing began as the procession strode into the synagogue. This was followed by the cantata “O how beautiful are thy tents, Jacob!” the Rheinischer Kurier reporter wrote of the event.

On the eve of the consecration, even King Wilhelm of Prussia, later German Emperor Wilhelm I, came to the (old) Kurhaus to listen to a concert by the Synagogue Singing Society and in this way pay his respects to the Jewish Community. The inauguration ceremony had been preceded by a farewell service in the old synagogue.

The 19th century: The long road to emancipation

The gradual civic equality of Jews began in the Duchy of Nassau, the new state of the Confederation of the Rhine, in 1806, when it abolished the “Leibzoll” (poll tax) for Jews under the influence of Napoleon. In 1817 Nassau was the first state in the German Confederation to introduce non-denominational schools, and in 1819 compulsory education for Jewish children. In 1841, the Jewish protection money was abolished. From 1842 on, the Jews of Nassau were given surnames. The next step was the introduction of compulsory military service in 1846. The liberal spirit of the revolution of 1848/49 caused a further push towards legal equality, in the wake of which further laws were formulated in Nassau for the equal rights of the Jews, even though there were also pogroms against the Jewish population in rural areas at the same time. In 1852, the duchy was divided into 83 synagogue districts. And now, in 1869, the emancipation of the Jews was unmistakably embodied in the Wiesbaden cityscape for all to see.

The central dome rose 35 meters high. A representative building in a prominent location. A few years earlier, Wiesbaden’s Protestants had still been considering whether to build a replacement for the Mauritius Church on the Michelsberg, which had burned down in 1850. They then decided on the site of today’s Marktkirche (1862). The name Michelsberg refers to St. Michael’s Chapel, which had stood in the cemetery there.

The new synagogue was an urban enhancement with exciting new visual perspecitves. The synagogue’s large onion tower was in dialogue with the towers of the Protestant Marktkirche and the Catholic St. Bonifatiuskirche. At the same time, the synagogue with its four small onion domes referenced the Russian Church on the Neroberg.

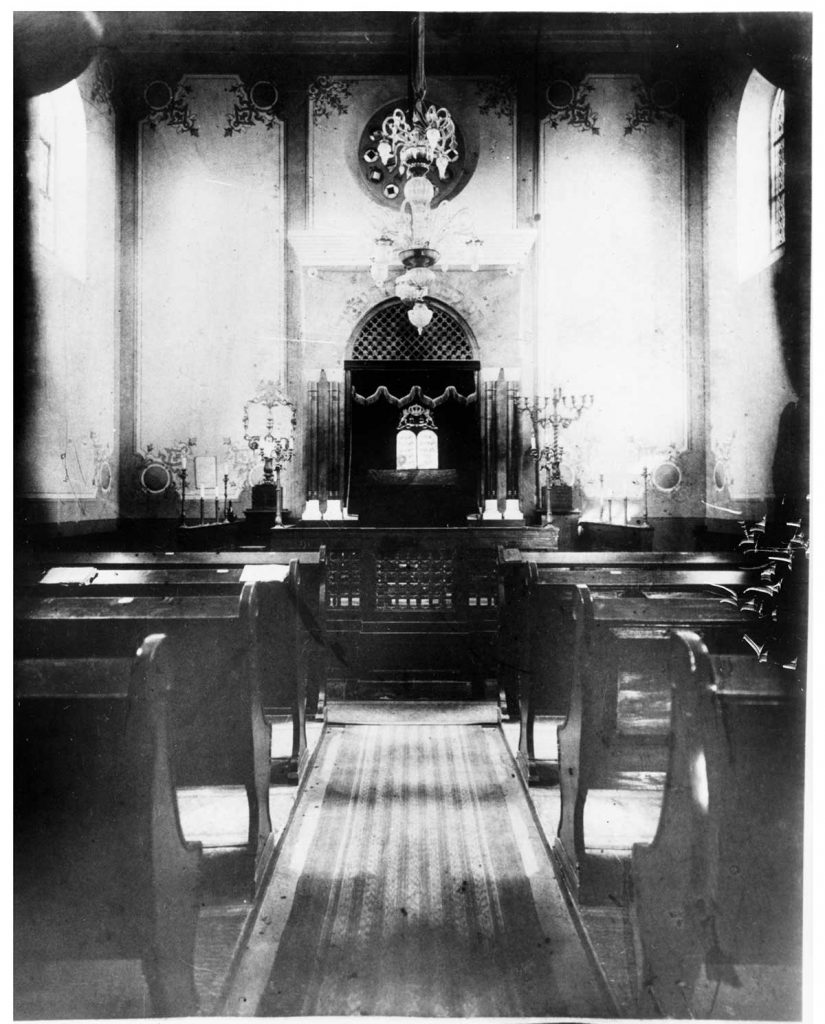

The design of the interior also followed the magnificent exterior design. Thus, the dome of the three-nave synagogue was decorated with gilded stars on a blue background. The four free-standing dome pillars, the half-columns and belt arches shone with their lavish ornamental decoration. The blue, gray, green and red decorated walls created a sacred atmosphere. The light streaming in through the central dome lent grandeur to the space. Through the small dome towers the women ascended to their gallery, the rabbi reached his room and the organist the organ. However, the women were also allowed to sit downstairs with the men. The pulpit in front of the apse was made of Nassau marble. Opposite it was the seven-branched candelabrum. Behind it, under a richly decorated canopy, was the Holy of Holies, the Torah shrine. Its marble columns supported a golden roof. Colored light entered through a round window and outshone the holy precinct. The canopy had similarities with the synagogue in the Oranienburger Strasse in Berlin, which was inaugurated in 1858. Philipp Hoffmann had masterfully solved the problem of creating an imposing structure on the relatively small building site. The Star of David not only shone above the main dome, it ran as a motif through the entire building, its ground plan and its facades.

With the Reich Constitution of 1871, German Jews became equal citizens in the then newly created empire. Legal security and a good measure of freedom enabled them to rise socially into the bourgeoisie. In Wiesbaden, many Jews worked as respected doctors and lawyers. Salomon Herxheimer (1842 — 1899), for example, was a specialist in skin diseases. His brother Karl Herxheimer (1861 — 1942) was director of the Municipal Skin Clinic, Privy Councillor of Medicine and bearer of the Iron Cross on the White Ribbon. Benjamin Wolff (1845 — 1892), a member of the Old-sraelite Religious Community, was the first Jewish city councilor in Wiesbaden. Later, in the 1920s, the conductor Otto Klemperer and the composer Ernst Krenek, the music director Otto Rosenstock and the opera singer Alexander Kipnis worked at the Wiesbaden Music Theater. Under the directorship of Paul Bekker, the musical life of the spa town enjoyed an excellent international reputation, also thanks to other numerous Jewish artists who lived at least temporarily in Wiesbaden.

Otto Klemperer, a native of Breslau, was one of the most important conductors of the 20th century and was Wiesbaden’s General Music Director from 1924 to 1927 under manager Carl Hagemann. Paul Bekker was general director of the Wiesbaden Theater from 1927 to 1932 and included quite a few contemporary works in his repertoire. Wiesbaden owes to him the revival of the May Festival, formerly the Kaiser Festival, in 1928. Although the artists were not part of the core of the Jewish community, they contributed to the prestige of Jewish Wiesbaden residents.

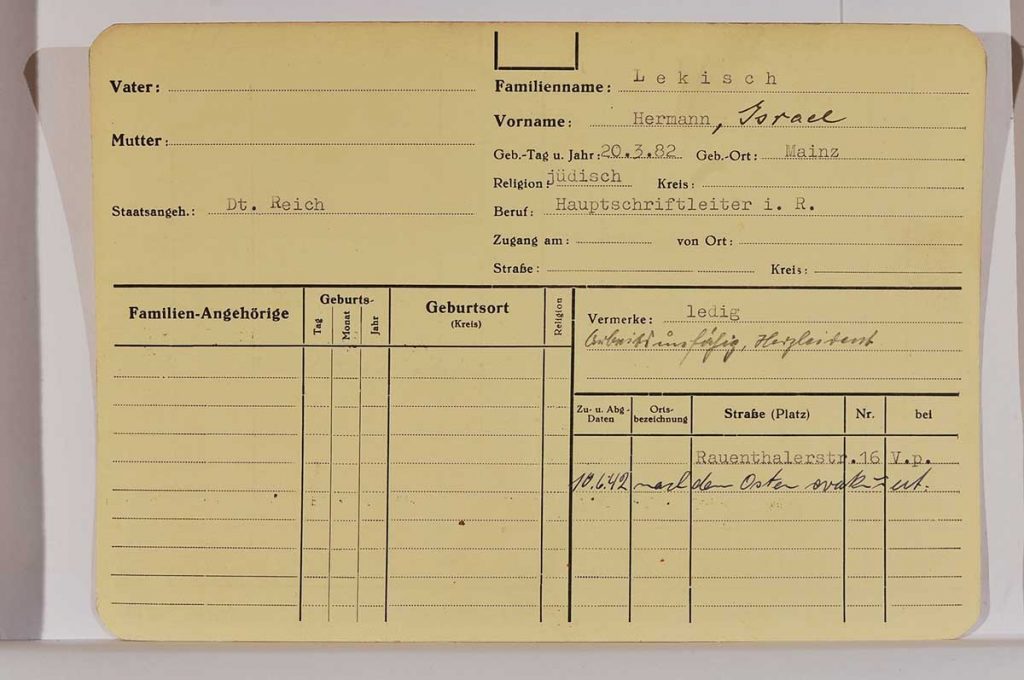

Among the Jewish personalities of the city was the editor-in-chief of the Wiesbadener Tagblatt, Hermann Lekisch, who also wrote plays on the side. The liberal-minded journalist was dismissed in 1933.

Together with his sister Emmy, he was deported to Sobibor in June 1942 and murdered in the gas chamber. Since October 2010, Hermann Lekisch has been commemorated by a “stumbling stone” in front of the Pressehaus at Langgasse 21.

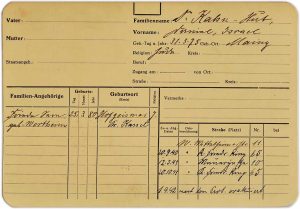

Gestapo file card of Hermann Lekisch. Last cynical entry: 10.06.42: Evacuated to the East.

(Illustration: Jewish Community Wiesbaden. StadtA WI NL 210 Nr. 1)

Liberal Judaism

It was also bourgeois liberal Judaism that shaped the spirit of the Jewish Community. Here Abraham Geiger (1810 — 1874) played a decisive role. Although he did not accompany the building of the synagogue as rabbi, as it was not built until after his departure from Wiesbaden, his ideas and impulses continued to have an effect on the community.

Following Moses Mendelssohn (1729 — 1786), Geiger tried to reconcile the new findings from science and technology with religion—reason and faith—much like the theologians Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768 — 1834) and Albrecht Ritschl (1822 — 1889) on the Protestant side. During his time in Wiesbaden, Abraham Geiger published the “Zeitschrift für jüdische Theologie” (“Journal of Jewish Theology”). Because the duke refused him the position of state rabbi, he finally saw no further possibility for effective activity in Wiesbaden and went to Breslau in 1838, later to Frankfurt am Main and finally to Berlin, where he taught at the Hochschule für Wissenschaft des Judentums (College for the Science of Judaism) from 1872. The consecration of the new synagogue on the Michelsberg was then performed by Rabbi Dr. Samuel Süßkind, who held his office in Wiesbaden from 1844 to 1884. The intellectual groundwork for the synagogue building, which was considered progressive by the standards of the time, was done by religious scholars such as Abraham Geiger. And Geiger did not miss the opportunity to be present at the dedication of the Wiesbaden synagogue.

Anti-Semitism was far less pronounced in the “spa and tourist town” of Wiesbaden in the 19th century than in some other small towns. However, with the influx of mostly poorer and Orthodox-oriented Jews from Russia at the beginning of the 20th century, most of whom settled in the Westend, tensions grew among Wiesbaden’s Jews. Conflicts arose between rich and poor, between “Eastern Jews” and established citizens, some of whom wanted nothing to do with the penniless newcomers; tensions also arose between Orthodox and liberal denominations. In 1925, about three percent of Wiesbaden’s population were Jews, and about a third came from Eastern Europe. Especially in the aftermath of the pogroms in Russia in the years 1903 to 1906, to which more than 2,000 people had fallen victim, many Jews from the East flocked to Western Europe.

There were also tensions, however, because the outward appearance of the Eastern Jews ran counter to the efforts of German Jews to conform in the period before the First World War.

Jewish businesses were a natural part of Wiesbaden’s cityscape in the early 20th century. In the Westend, for example, Ephraim Tiefenbrunner owned a store at Herrmannstrasse 3. He sold kosher sausage, which he obtained via overnight express from a Berlin slaughterhouse. His competitor was Isaak Altmann at Helenenstrasse 33. Between 1905 and 1928, many Jews from East Central Europe also flocked to Wiesbaden, especially from Polish Galicia, which had belonged to Austria-Hungary until 1919. Many who lived in the Westend between Schwalbacherstrasse and Scharnhorststrasse, Emserstrasse, Bertramstrasse and Goebenstrasse were related to each other. They spoke Yiddish, a language similar to Middle High German with Slavic and Hebrew elements and Hebrew writing. Even though they formally belonged to the Jewish Community on the Michelsberg, they had their own prayer houses, called “Stibl” in Yiddish. About 25 families counted themselves among the particularly pious Hasidim.

One of the successful Wiesbaden businesses was run by the Jewish factory owner Dr. Leopold Katzenstein. Born in Thuringia, the doctor ran the “Pharmaceutical Industry Dr. Katzenstein” in Erbenheim. The “children’s risinettes” (cold pills) they produced were useful against pharyngeal , laryngeal and bronchial catarrh. Leopold Katzenstein was murdered in Sachsenhausen concentration camp, his wife Dorothea in Auschwitz.

Jewish Wiesbaden was a diverse cosmos. Its social spectrum ranged from the inconspicuous poor employee with no income to the respected upper middle-class.

Reform Judaism and Old-Israelites: The schism

The liturgical rapprochement with the Christian rite through the “organ synagogue” on the Michelsberg, however, was too much reform and adaptation for the (religious-)law-abiding among the congregation members. From the point of view of the “pious”, the “liberals” had moved too far away from the forefathers. The Orthodox disapproved of both the installation of an organ and the existence of the synagogue singing society, founded in 1863, in which women were also allowed to participate, and insisted on a clear separation from the Christian-influenced environment. The fact that the liberals no longer observed the rules of Shabbat also met with disapproval. In 1878, about 40 families left the Jewish Community and founded the Old-Israelite Community (Alt-Israelitische Kultusgemeinde). One of the first “withdrawal communities” in Prussia, it built its own synagogue in the Friedrichstraße, which was inaugurated in 1897. Here the service was again organized according to the (religious-)law-abiding tradition.

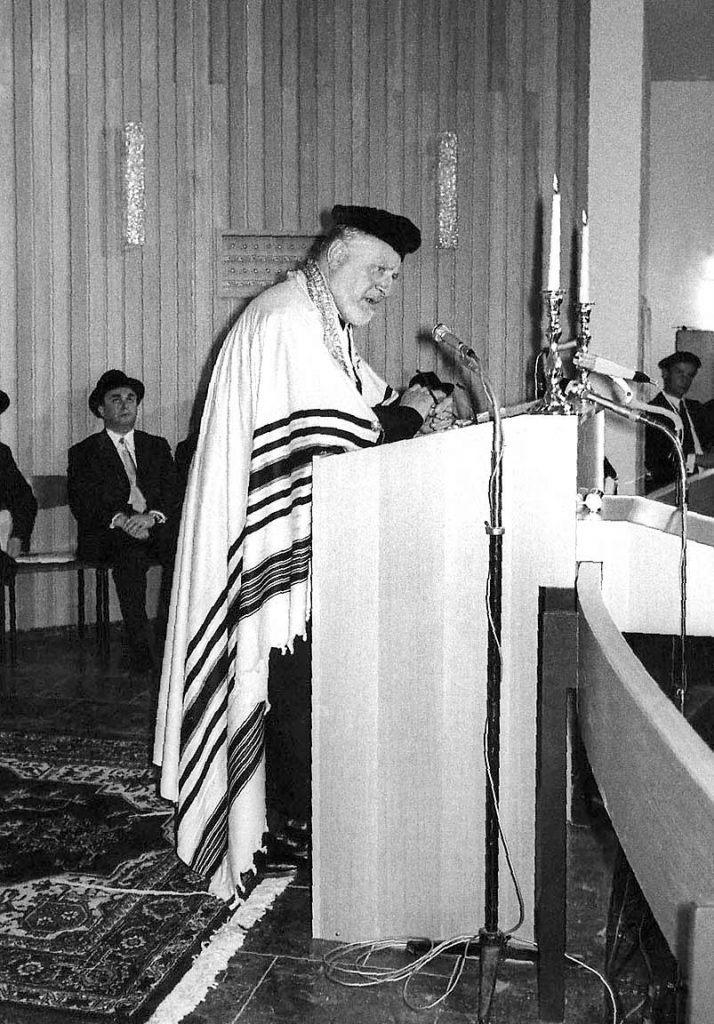

For half a century, from 1876 to 1925, Rabbi Dr. Leo Kahn (1888 — 1951) shaped the religious life of the Old-Israelites.

“The first thing I need is a mikvah,” Kahn, who came from Sulzburg in Baden, is said to have said upon his arrival in Wiesbaden.

For there was no longer a ritual bath in the synagogue on the Michelsberg. So the Orthodox Jews revived the old mikvah at Spiegelgasse 9. Today, this building houses the Paris Court Theater and the Spiegelgasse Active Museum of German-Jewish History. Of Kahn’s successor, Dr. Jonas Ansbacher (1879 — 1967), who came from Nuremberg, the statement has come down to us that Kahn “protected his congregation like an eagle protects its nest”, in deep piety, great erudition and stunning eloquence. Ansbacher was rabbi of the Alt-Israelitische Kultusgemeinde from 1925 until the end of 1938. He was temporarily interned in the Buchenwald concentration camp. In 1939 he managed to escape to England. From 1941 to 1955 he was rabbi at a synagogue in London.

Paul Lazarus (1888 — 1951), the rabbi of the Israelite Community, attested of him: “From the intrepid fighter in his early tenure, he had become the symbol of peaceful coexistence between the two communities.” Kahn died at the biblical age of 94, highly respected by Jews and Christians alike. On his tombstone, two blessing hands attest to his descent from the Jewish priestly lineage.

Paul Lazarus was a bridge-builder: between orthodox and liberal, poor and rich Jews. He was particularly committed to the integration of Eastern Jews and to welfare work. After Jewish children were no longer allowed to attend public schools during the National Socialist dictatorship, he saw to the establishment of the school in the Mainzer Strasse, which opened in 1936.

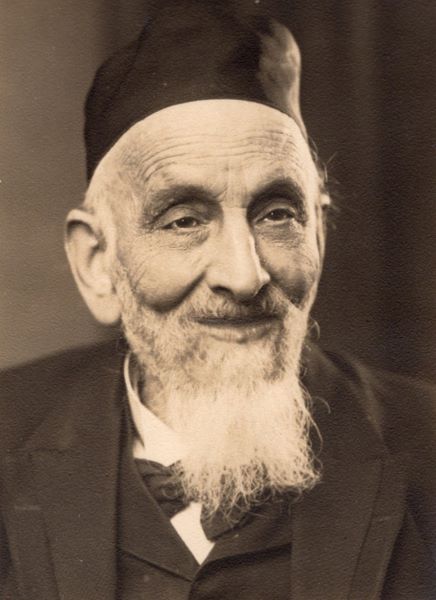

The rabbi of the Old-Israelite Community:

Dr. Eliezer Leo Lipman Kahn

(Illustration: Miriam Kraisel, granddaughter of Rabbi Dr. Kahn)

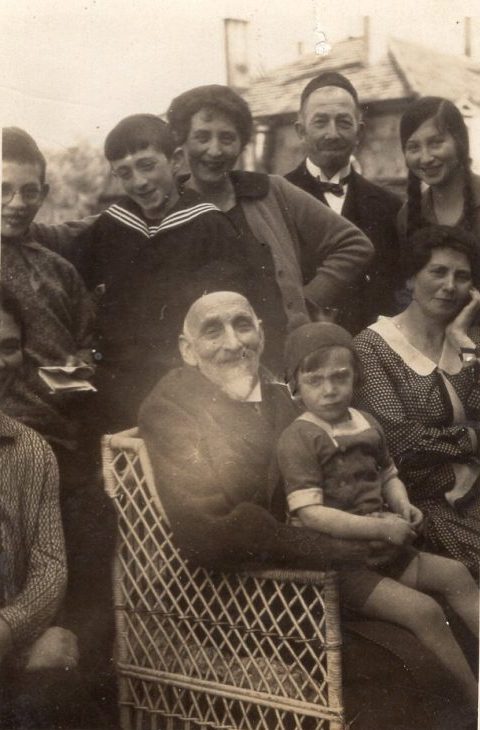

Rabbi Dr. Eliezer Leo Lipman Kahn with his family

(Illustration: Miriam Kraisel, granddaughter of Rabbi Dr. Kahn)

Kahn’s successor: Rabbi Dr. Jonas Ansbacher

(Illustration: Active Museum Spiegelgasse)

Visitors from all over the world: The Jewish cemeteries

In 1750, the first Jewish cemetery was established on the Kuhberg in the Idsteiner Straße, today Schöne Aussicht. Until then, Wiesbaden Jews had been buried in Wehen. From 1750 on, the area on the Kuhberg was also the burial place for the surrounding communities. In 1883, among others, Ephraim Ben Abraham Schönberger was buried here. His gravestone reads, “He was a respected and God-fearing man with all his heart.” The Duke’s Privy Councillor of Commerce Marcus Berlé, who had made it from glazier to founder of a successful banking house and was a great supporter of the Michelsberg synagogue, may have been at least as respected. In 1890 the cemetery on the Kuhberg was closed. But to this day people from Israel, the USA and all over the world still come here to visit the graves of their ancestors.

After the Old-Israelite Community was founded, it established its own cemetery on Hellkundweg in 1877. Due to the closure of the area at the “Schöne Aussicht”, the cemetery in the Platter Straße was inaugurated in 1891 for the Jewish Community, both in the immediate vicinity of the Christian North Cemetery. Among others, the actress at the Wiesbaden theater Luise Wolff (d. 1917) and the department store founder Julius Bacharach (d. 1922) are buried at Hellkundweg. Today’s Jewish community buries its dead in the cemetery in the Platter Strasse. Jewish cemeteries also exist in the suburbs of Bierstadt, Schierstein and Biebrich, as well as in Walluf. But they are no longer used.

Between Integration and Incitement: Jewry between the Wars

The period between the world wars, during the Weimar Republic, was ambivalent for Wiesbaden’s Jews. On the one hand, Germany’s defeat in the war of 1918 and the economic hardship that followed caused a new, intensifying anti-Semitism; on the other hand, there were plans in Wiesbaden to create a modern Jewish community center at today’s Platz der deutschen Einheit and to further integration.

Economic decline, the provisions of the Versailles Peace Treaty (1919), which were perceived as extremely unjust, and the humiliation inflicted by French occupation forces also fostered an anti-Jewish climate in Wiesbaden. Once again, Jews had to be used as scapegoats. Right-wing extremists in particular portrayed Jews as responsible for the defeat of the German Reich in World War I and incited against them in the same breath as the “November criminals.” This referred to the “Weimar parties” SPD and USPD, the liberal German Democratic Party (DDP) and the Catholic Center. Exemplary for the patriotism of German Jewry was Walter Rathenau (DDP), who as Minister of Reconstruction in 1921 pushed through reparation relief against France in the “Wiesbaden Agreement.” In 1922, Rathenau was assassinated in Berlin by right-wing enemies of the Republic.

The economic crises of the 1920s also took their toll on the previously prosperous Jews of Wiesbaden. In 1922, the community set up a “middle-class kitchen” for its impoverished members, followed in 1924 by the construction of an “Israelite old people’s home” at Geisbergstrasse 24. A “welfare center” based on the model of the Inner Mission had already existed since 1917. An association for Jewish vacation colonies made it possible for children of destitute parents to spend recreational time in the countryside.

The dark November night of 1938: A tragedy in five acts

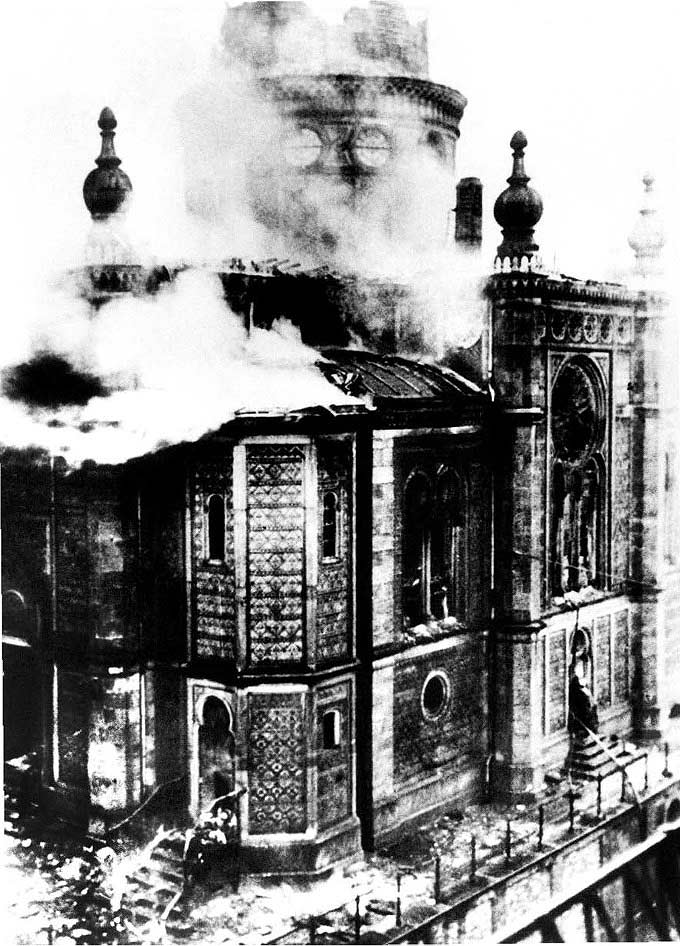

The tragedy of November 10, 1938, in which SA and party squads destroyed the synagogue on the Michelsberg, can, in retrospect, be divided into five acts.

Act I, on the evening of November 9: Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels takes the attack by the Jew Herschel Grünspan on the diplomat Ernst vom Rath in Paris on November 7 as an opportunity to issue instructions to the party branches for a “spontaneous” reaction. NSDAP and SA men dressed in civilian clothes entered the Wiesbaden synagogue at night. They threw the Torah scrolls into the air, tore up prayer books, stole what they thought was somehow valuable, and set fire to the synagogue.

Act Two: Around 4 o’clock in the morning, the fire department arrived and began to extinguish, probably due to misunderstandings.

Third act: Around 6 o’clock, a Nazi commando appeared again, again in plain clothes, to feign spontaneity; in reality, the instructions had come from Berlin. Using accelerants, the synagogue was set on fire again. This time the fire department had apparently received clear instructions from the party: Protect only the neighboring buildings. The police stood idly by. This is how Georg Buch (1903 — 1995), the later SPD mayor of Wiesbaden, described the events of the night.

Fourth act: Around 8 o’clock, a crowd gathered at the Michelsberg. Some were armed with axes and crowbars. They smashed the benches in two and piled them up into a pyramid. Apparently, the synagogue was not burning fast enough for them. They doused the wooden pyramid with gasoline and set it on fire. The building was now ablaze. The flames also spread to the neighboring community center. The fire was still smoldering in the afternoon of November 10. No one protested, at least not publicly. According to witnesses, passersby were as shocked as they were silent.

Act Five: In the afternoon, around 2 p.m., the dome collapsed.

A prey to the flames: the synagogue at noon on November 10, 1938.

(Illustration: HHStAW Best. 3008,1,1, 3997)

In blind zeal: the mob rages in the stores

While the synagogue burned, Jewish stores in the city center were demolished. Among many others, the hat store Ullmann, the wine store Simon and the jewelry store Heimerdinger, in addition to the fashion store for children’s clothing Baum in the Webergasse, the perfumery Albersheim and the shoe store Mesch. The company Salberg—glass and crystals—at the entrance of the Langgasse was also attacked. A few houses further on, the rioters hurled shoes indiscriminately onto the street from a shoe store.

The devastation always followed the same pattern: the destruction squads smashed windows and doors, then demolished the stores and threw the merchandise onto the street. “Germans do not buy in Jewish stores,” was written on the cardboard signs that SA squads hung on the houses. In blind zeal they smashed the windows of the Jewish stores. Nothing was seen of the police.

The apartment and office of the lawyer Berthold Guthmann were also vandalized. “The people threw the files out the window, destroyed the furniture and smashed window panes,” stated an indictment filed with the Wiesbaden Regional Court in 1950. Guthmann was arrested and taken to the Buchenwald concentration camp, where he was held for six weeks and severely maltreated. After his release, he returned to Wiesbaden. Here he took over the presidency of the Jewish “Einheitsgemeinde” (unity community) and helped many community members to emigrate. He himself stayed until he was forcibly transferred to Frankfurt in November 1942, from where he was finally deported and murdered in Auschwitz in 1944. He had already lost his license to practice law in 1933. In World War I, Berthold Guthmann had been a flight lieutenant and awarded the Iron Cross. Guthmann did not take opportunities to bring himself and his family to safety abroad. As a member of the board of the Jewish community and representative of the “Reich Association of Jews in Germany,” he remained with his community, whose members he supported to the best of his ability until the last major deportation in 1942. Guthmann was forced to cooperate in the dissolution of the community and the “Reichsvereinigung” (Reich Association of Jews in Germany). He also had to compile the lists for the deportations.

In the famous store for ladies’ fashions of Carl Bacharach (1869 — 1938) in Webergasse 2 — 4 even Kaiser Wilhelm II had once been a customer. The businessman and his wife Anna were arrested in March 1939.

Carl Bacharach died in the remand prison in the Albrechtstraße. Bacharach’s house at Alexandrastraße 6 — 8 was one of a total of 42 “Jewish houses” in which Wiesbaden’s Jewish population was isolated from the beginning of the war. In 1943, the last Jewish houses were dissolved.

For months, the ruins of the synagogue on the Michelsberg bore witness to the atrocity. It was not until the summer of 1939 that it was finally demolished. Finally, in 1950, the base of the synagogue was demolished and the Coulinstrasse was widened. Now nothing reminded one of the former location of the synagogue.

The rubble of the suburbs: Five synagogues desecrated in Wiesbaden.

Five synagogues were desecrated and ruined by the Nazi destruction squads in Wiesbaden on November 9/10, 1938: two in the city center (Michelsberg and Friedrichstraße) and the synagogues in Bierstadt (built in 1827), Schierstein (1858) and Biebrich (1860). In the case of the synagogue in the Friedrichstraße, arson was not used, probably because there was a danger of the flames spreading to neighboring houses. The National Socialists also rampaged in the small prayer house at Blücherstraße 6, where the Orthodox Eastern Jews from the neighborhood gathered, but no fires were set there, presumably because of the cramped conditions of the building. The synagogue in Biebrich, which was also demolished in 1938, fell victim to a bombing raid during the war. The ruins of the Bierstadt synagogue were demolished in 1971.

Ordered in Berlin: An organized state crime

For Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, the assassination of Ernst vom Rath in Paris was a welcome opportunity to herald a new stage in the persecution of German Jews. Without even mentioning the burning of the synagogues, the Nassauer Volksblatt, published in Wiesbaden, claimed the day after the outrage: “Whoever walked through the streets could hear how deep the anger sat in the people over this nefarious and vile act of Jewry.” And further, “If damage then occurred in some places, the Jews brought it on themselves.” The Tagblatt expressed itself in similar terms. It also avoided references to the destruction and stated threateningly that the “damages” were to be regarded “as a reminder that could not be expressed more forcefully.”

In 1946, the main perpetrators of the Pogrom Night in Wiesbaden were brought to trial, but were only mildly punished. Although the law provided for a sentence of not less than ten years in prison for aggravated arson, only sentences of between two and five years were imposed.

Long before the November pogroms, two Wiesbaden Jews had been murdered by Nazis: In April 1933, they killed 39-year-old milk merchant and SPD treasurer Max Kassel at Webergasse 46 and 58-year-old merchant Salomon Rosenstrauch at Wilhelmstrasse 20. While Rosenstrauch succumbed to a heart attack as a result of an assault, Kassel was shot with a pistol. Although the perpetrators were prosecuted, they were punished very leniently.

In the spring of 1938, the Jews of Wiesbaden had to declare all their assets, and in October 300 Polish Jews were deported to Poland. Almost all of them became victims of the Holocaust.

From Arson to Mass Deportation: The Start of the Machinery of Genocide

On January 20, 1942, the “Wannsee Conference” on the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question” took place in Berlin. The German Jews, who had been without rights at least since the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, were to be deported to Eastern Europe and killed there. A first wave of arrests had already seized Wiesbaden Jews in October 1938. On October 17, Rabbi Paul Lazarus held his last sermon in the Michelsberg synagogue. Forebodingly, he said, “This time has taught us to say goodbye.” Lazarus was temporarily deported to a concentration camp after the November pogroms. In 1939, he fled to Nice and emigrated from there to Palestine. Impoverished, he died in Israel in 1951. After the destruction during the “Reichskristallnacht”, the Jewish Community was allowed to hold its services in the Friedrichstraße for a while. Paul Lazarus’ library of 1,700 volumes was given to the Förderkreis Aktives Museum deutsch-jüdischer Geschichte in Wiesbaden by his daughters Eva and Hanna in 1999.

The mass deportations from Wiesbaden began on June 9, 1942, after which just under 600 Jews still lived in the city. In 1933, there had still been about 2,800. Emigration was no longer possible after October 1, 1942. The last major deportation took place on September 1, 1942. On a Saturday, Shabbath of all days, on August 29, about 370 Wiesbaden Jews had to gather in the courtyard of the partially destroyed synagogue in the Friedrichstraße. They were allowed to take only a small suitcase and a maximum of 50 Reichsmark with them. Their remaining assets had been confiscated. In the synagogue they had to spend a night of perplexity and despair. They had been told that they would be “housed together outside the Old Reich”. But hadn’t Hitler already spoken of the “annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe” in 1939?

From the Friedrichstraße, the mainly elderly Jews moved on foot in the direction of the slaughterhouse, where they were herded together at the cattle loading ramp and then herded into the waiting Reichsbahn railroad cars. Like cattle, they were sent on the journey to their deaths. Via Frankfurt am Main to Theresienstadt and from there to the large murder factories in the East. They even had to pay for this transport to death. Not many Wiesbaden residents took care of the persecuted. Almost 100 of Wiesbaden’s Jews avoided deportation by committing suicide.

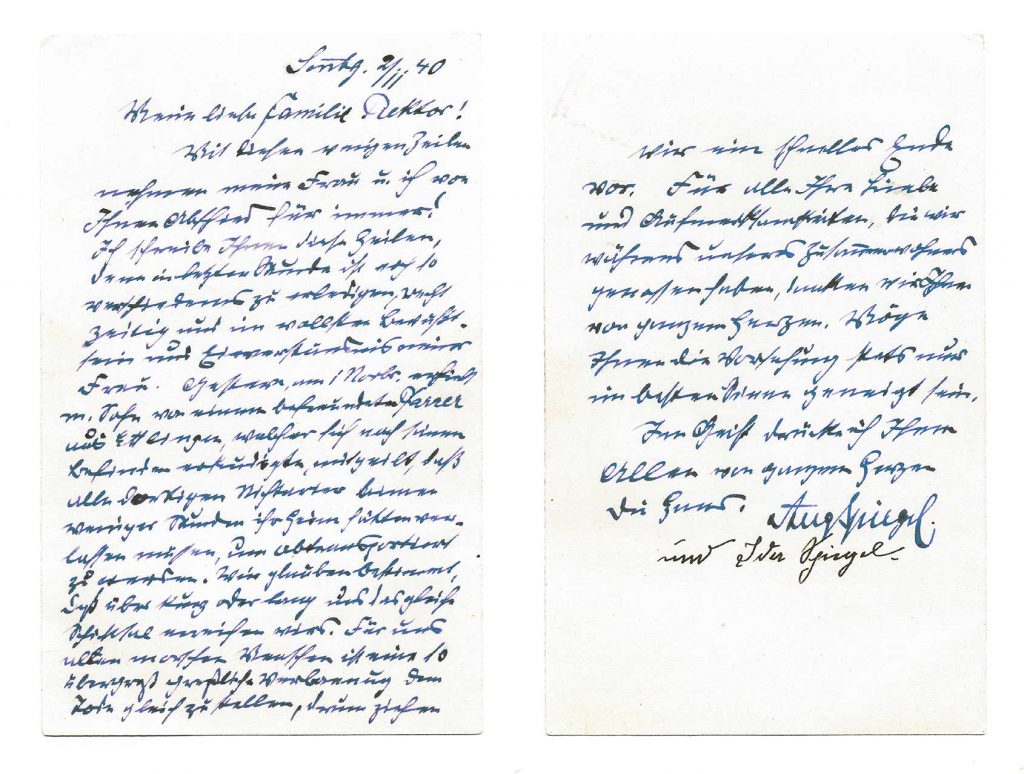

Transcription of the farewell letter

Sunday 2.11.40

My dear Rector family! *

With these few lines my wife and I take leave of you—forever! I am writing you these lines because at the last hour there are still so many things to be done, in time and with the fullest consciousness and consent of my wife. Yesterday, November 1, my son was informed by a priest friend from Ettlingen, who inquired about his condition, that all non-Aryans there would have had to leave their homes within a few hours in order to be deported.

We certainly believe that sooner or later the same fate will reach us. For us old, rotten people, such an overly ghastly banishment is equivalent to death, so we prefer a quick end. We thank you from the bottom of our hearts for all your love and attention we enjoyed during our living together. May Providence be always inclined to you only in the best sense. In spirit, I press all your hands with all my heart.

August Spiegel and Ida Spiegel

* Nikolaus Prediger was a rector at Wiesbaden schools.

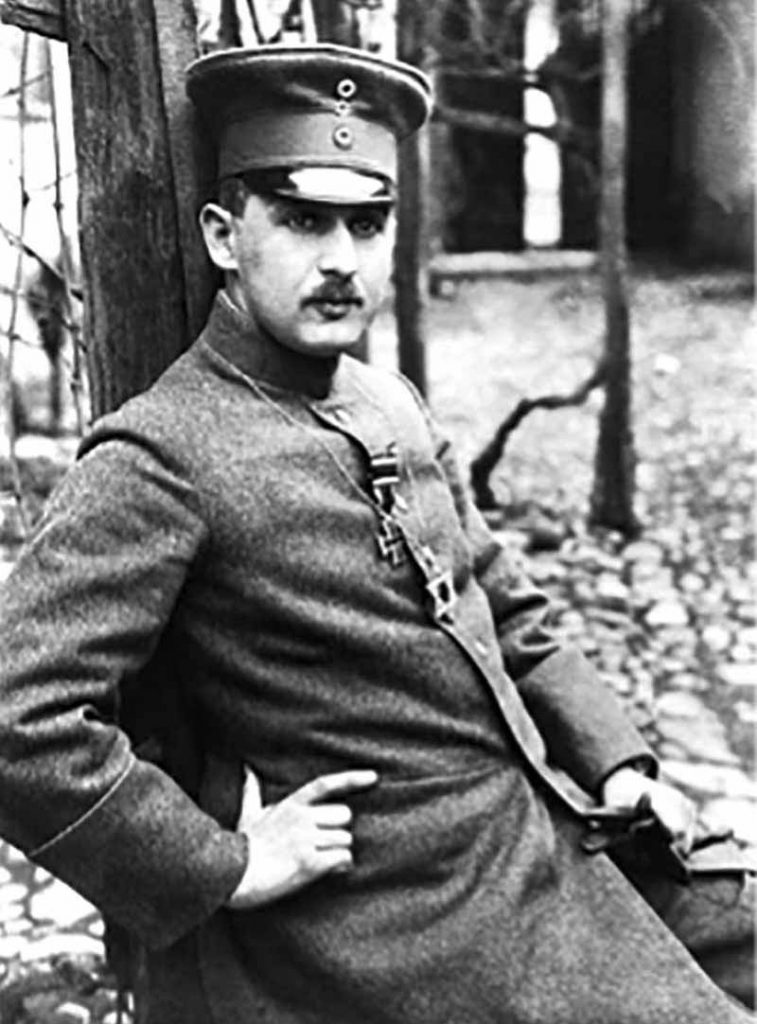

A boulder bears their names: The forgotten fighters

Even their participation in World War I (1914 — 1918) did not save German Jews from the gas chambers. A total of 57 Jewish soldiers from Wiesbaden—many of whom had been awarded the Iron Cross—lost their lives in the trenches of the Western and Eastern Fronts during this war. Measured against the number of about 2,000 Jewish Wiesbadeners around the year 1914, this was even a disproportionately high blood toll among the Wiesbaden population. A commemorative plaque on a boulder in the Jewish Cemetery in the Platter Strasse commemorates the fallen.

On May 22, 1921, the honorary plaque was ceremoniously unveiled by Rabbi Paul Lazarus. He too had enlisted as a war volunteer and field rabbi in 1916 and was on duty in Macedonia. When the bells of the Wiesbaden churches rang out in August 1914, the Jews of Wiesbaden also prayed in the synagogues for the victory of their fatherland. At the end of 1932, the Wiesbaden chapter of the Reichsbund Jüdischer Frontsoldaten still had 105 members. After the transfer of power to Hitler, they were spared for a while, but from 1936 on they were no longer spared. They were forbidden any political activity and in 1938 the Reichsbund was dissolved.

Names such as Karl Hamburger (1891 — 1915), Sigmund Helfer (1877 — 1917) and Theodor Abraham (1880 — 1918) are inscribed on the honorary plaque in the Jewish cemetery. The fact that Wiesbaden Jews were just as willing as many others to sacrifice their lives for their fatherland in the First World War is hardly present in the collective memory. Apart from the memorial plaque at the Jewish cemetery, nothing in the Wiesbaden cityscape reminds us of their fate.

No quarter for legal scholars: Jewish jurists

The fates of Jewish jurists, which Wiesbaden jurist and local historian Dr. Rolf Faber has researched and published in the series of publications of the city archive, are also moving and poignant. There were several dozen Jewish judges, state attorneys and lawyers in Wiesbaden during the Weimar Republic. Dr. Wilhelm Dreyer (1882 — 1938), who is mentioned here as a representative example, was a judge at the Higher Regional Court in Frankfurt am Main. He was shunted to the Wiesbaden Regional Court in 1933 and retired in 1935. On November 10, 1938, unsuspectingly, he was ordered to report to police headquarters in the Friedrichstrasse. There he was arrested and deported to the Buchenwald concentration camp together with other Wiesbaden Jews. Dreyer died on November 25, only two weeks after his committal. He was one of 26,000 Jewish men arrested throughout the Reich in accordance with the instructions of Reinhard Heydrich, the head of the security police.

Wilhelm Dreyer was not the only Wiesbaden resident whose family had converted from Judaism to Protestantism in the late 19th century. Dreyer was also a soldier in World War I, with the rank of lieutenant. But neither his Protestant faith nor his participation in the war protected him from being murdered. His “crime” was solely that he belonged to the “Jewish race.”

The disenfranchisement of Jews after the Nazi “seizure of power” took place in several stages: As early as April 1933, the “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service” created the basis for removing politically disfavored and Jewish civil servants from the civil service. According to the “Nuremberg Race Laws” of 1935, no Jew was allowed to hold public office any longer; his citizenship was practically revoked. Jurisprudence and the separation of powers had been annulled in Germany anyway. For in 1933 Hitler had declared himself the “supreme ruler” of the German people.

Humiliation and exclusion reached a new level in 1941: From September onwards, all Jews in the Reich and in the occupied territories had to wear the “Star of David”. The Star of David, which had been visible from afar on the dome of the Wiesbaden synagogue since 1869, had become a stigma. Its bearers were without rights and dignity.

After the Liberation in 1945: The Star of David shines again in the city

During the time of National Socialism, a crime of almost unimaginable dimensions was committed against the European Jews, which only very few Jews survived.

As early as 1945, the Jewish community in Wiesbaden began to form anew under the protection of the Americans. In 1946, after much work of its own in rebuilding, it was able to consecrate the synagogue in the Friedrichstraße again.

The initiator of the reestablishment of the community was Claire Guthmann, the widow of the lawyer Berthold Guthmann, who had been murdered in Auschwitz. She and her daughter Charlotte were the only members of her family to survive the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Claire Guthmann had returned to Germany as a “displaced person” and initially lived in a camp, but was soon assigned a room in Wiesbaden. On July 21, 1945, the municipal “Care Center for the Politically, Racially and Religiously Persecuted” informed the U.S. military government about the reestablishment of a Jewish community. Claire Guthmann was its first spokeswoman and took care of the members from the former Jewish old people’s home at Geisbergstraße 24. In 1946, Dr. Leon Frim from Lemberg became chairman of the community. Frim had survived the concentration camps Auschwitz and Buchenwald. Jakob Matzner was one of the co-founders of the Jewish Community.

On Hanukkah, December 22, 1946, the synagogue was rededicated in a ceremonial act. Colonel James R. Newman, the man who had proclaimed Wiesbaden the capital of the new state of Hesse in 1945, spoke on behalf of the U.S. military government. Mayor Hans Redlhammer (CDU) participated on behalf of the city. The American military rabbi William Dalin lit the lights of the Hanukkah candelabrum. The only Torah scroll saved during the desecration in November 1938 returned to Wiesbaden from its “exile” in Switzerland on this day. With Chaim Hecht, the community now had its own rabbi again.

A rebuilding of the old synagogue or the construction of a new one on the Michelsberg was first considered, but then dropped.

In the 1960s, the synagogue in the Friedrichstraße no longer met the needs of the community, which now decided to build a new one. The foundation stone was laid in 1965, and the synagogue was consecrated in 1966. The state rabbi Dr. Isaak Emil Lichtigfeld was present at its consecration. Minister President Georg August Zinn (SPD) spoke on behalf of the state of Hesse, and Lord Mayor Georg Buch (SPD) congratulated the congregation on behalf of the city of Wiesbaden. Buch himself had once been a prisoner in the Hinzert and Sachsenhausen concentration camps.

The modern building designed by architects Helmut Joos and Ignaz Jakoby is characterized by the windows of Wiesbaden sculptor and glass designer Egon Altdorf. Blue, ruby red and golden yellow tones dominate. Only the Burning Bush shines in green. The colors change throughout the day depending on the exposure to light. The purple hues that appear at dusk disappear again the next day.

You can find out more about the post-war history of the Wiesbaden Jewish Community in the online exhibition: “Jewish Wiesbaden: Between a New Beginning, Confidence and “Tarbut — Time for Jewish Culture”.

Jewish Community in Transition: Immigrants from the Former Soviet Union

In the early 1990s, the number of community members increased by leaps and bounds as emigrants from the former Soviet Union moved in. As a result, community life gained a new dynamic. The previously somewhat ageing congregation once again enjoyed many children. The integration of the Russian-speakers is giving the community a lot of work, but Wiesbaden’s commitment is considered exemplary throughout the republic, not least thanks to the support of the Central Welfare Office of Jews in Germany, based in Frankfurt. And, says Jacob Gutmark, looking at the new “Jews from the East” in comparison with the inner conflict of German and Eastern Jews in the 1920s, “This time we must not fail, or soon there will be no Jewish communities left.”

In 2023, Wiesbaden’s Jewish community will have close to 850 members. That makes it one of the fastest-growing communities in Hesse, after Kassel and Offenbach. But there are hardly any German Jews left. The majority consists of migrants. Quite a few of them have gone through concentration camps in several countries.

Since then, teaching Jewish content and values to those who grew up in an atheistic state has been one of the community’s most distinguished tasks. Today, two thirds of its members come from countries of the former Soviet Union.

A social worker and an integration assistant take care not only of them, but also of well over two thousand family members who are not members of the Jewish Community.

Their homeland lies between the Gulf of Finland and the Black Sea, which they left for Germany. Many are doctors, artists, engineers. Some did not speak a word of German when they arrived, some only a few scraps of Yiddish. But why are they emigrating to Germany of all places? Dr. Jacob Gutmark is often asked this question. His answer: “Since the war, word has spread that you’re no longer persecuted in Germany and that you can succeed here.” In Russia, on the other hand, the situation for Jews today is still quite difficult in some places.

With learning circle and culture club: Lively community life

The community center in the Friedrichstrasse is a hive of community activity. People continue their education in religious topics, learn German and Hebrew, partly in tandem courses. People practice gymnastics and self-defense, play chess, table tennis and basketball in the TuS Makkabi Wiesbaden. State-recognized religious instruction is given from the first grade of elementary school through high school graduation. People meet for learning in the community center, in the Tom Salus learning circle and in the culture club. There is swimming for senior citizens and a “meeting place” for Holocaust survivors. More than a hundred volunteers actively participate in community life. Anita Lippert, née Fried, born in 1931, is the last member of the Wiesbaden congregation who had visited the Jewish school in the Mainzer Straße and was later transported from the slaughterhouse ramp to Theresienstadt.

The congregation’s “Mitteilungsblatt” is published regularly—in German and partly in Russian—with contributions of all kinds. Among the important rites is the service on Shabbath, the seventh day on which God rested after the creation of the world. The service is followed by a festive meal together. But all other Jewish holidays are also celebrated here.

The Wiesbaden synagogue is also visited by Christian communities for information, especially school classes. There are over 80 groups of visitors a year. The Jewish community sees itself as a unified community and the legal and moral successor to the pre-war community. It celebrates its services according to the Orthodox rite. The “liberals” can also participate in it. Conversely, however, the Orthodox would never participate in a liberal service.

Former Wiesbaden Jews and their descendants now live scattered across all continents. Since the 1970s, they have been regularly invited by the state capital Wiesbaden to visit. The Active Museum Spiegelgasse for German-Jewish History in Wiesbaden (AMS) also maintains intensive contacts with numerous Wiesbaden Jews and their families living abroad, not least in order to research their biographies, but above all the biographies of those who were once murdered.

For a long time, over a quarter of a century, Cantor Avigdor Zuker shaped the life of the community. Most recently, he also taught at the Hochschule für Jüdische Studien (College of Jewish Studies) in Heidelberg. Since 2000, Avraham Zeev Nussbaum has been cantor, and since 2004, after receiving further training in Jerusalem, cantor and rabbi of the congregation. Since the early 1980s, Dr. Jacob Gutmark, born in 1938, has been a member of the four-member board. He gives the congregation a face in the city and lends it weight. Gutmark looks after internal matters, culture and religion, as well as representing the community’s interests in terms of representation and content. Since 2007, there has been a city contract between the state capital and the Jewish community.

Today, the community is present in the city life in many ways. Since 2008, it has organized the event series “Tarbut—Time for Jewish Culture” with a wide range of offerings, from a performance by an Israeli youth brass orchestra from Wiesbaden’s partner city Kfar Saba in Israel to Israeli films at the Caligari, literary readings at the Villa Clementine, and an exhibition on various topics at the city hall.

In 2020, the Jewish Community Wiesbaden was awarded the “Prize for the Promotion of Cultural Life”, the Cultural Prize of the state capital Wiesbaden for its series of events.

In 2013, the Jewish Teaching House (“Jüdisches Lehrhaus”) was also newly founded. It offers events on various aspects of Jewish culture and identity, imparts Jewish knowledge and addresses historical topics.

The Jewish Community’s charter states that children and young people are to be educated religiously and culturally and “in love for the Jewish people.”

Since 2006, Steve Landau has been the executive director responsible for the community’s operations. He is also the director of the Jewish Teaching House.