Memorial for the murdered Jews of Wiesbaden

(Photographer [FranzXaver] Süß)

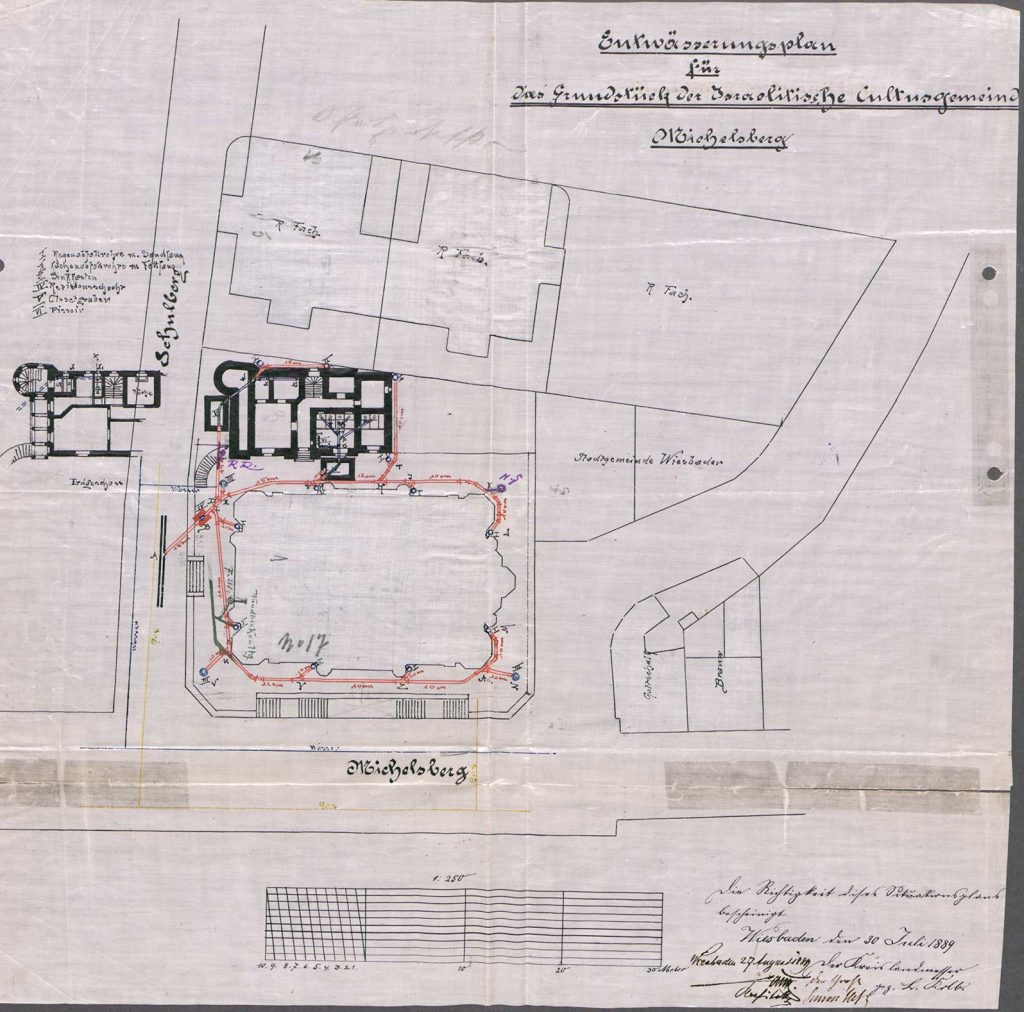

The location of the synagogue: Drainage plan for the site of the synagogue from 1889.

(Illustration: StadtA WI WI/2 Nr. 4902)

The way to the memorial

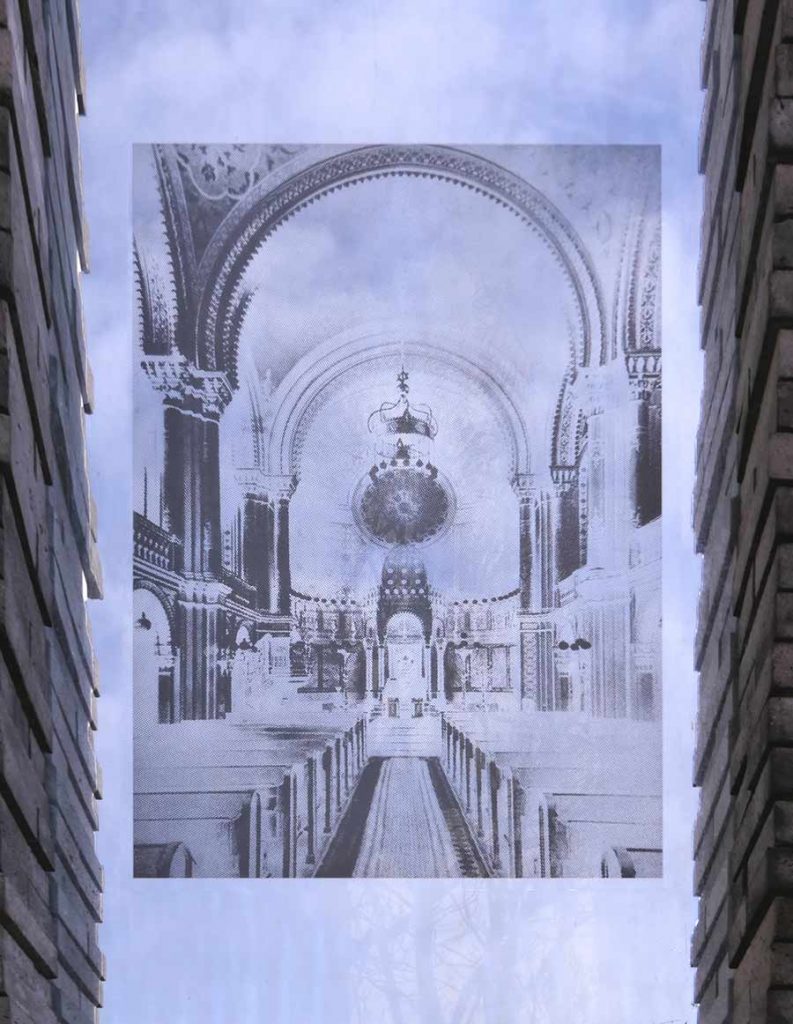

There on the Michelsberg, where the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Wiesbaden is located today, the new synagogue had stood since 1869: a magnificent building by the architect Philipp Hoffmann in Byzantine style. In the Reichspogromnacht of November 9, 1938, it fell victim to arson and complete destruction. After the end of the 2nd World War nothing was left of it. Only a stele from 1953 recalled its old location. Already in the 1950s, the Coulinstraße led through the middle of the old ground plan of the destroyed synagogue.

At the beginning of the 1970s, the synagogue seemed to have been forgotten when the city of Wiesbaden — following the zeitgeist of the car-friendly city — had an elevated bridge built for automobile traffic from the neighboring Schwalbacher Strasse to the Coulinstrasse, which ran across the former synagogue property. It was only 30 years later, when attitudes to urban planning had changed and, as a result, the elevated bridge was demolished, that the way was cleared to deal with the redesign of the synagogue square on the Michelsberg.

Commemorating the Jewish victims of the Holocaust from Wiesbaden by name at the site of the former synagogue had long been a special concern of the Active Museum of German-Jewish History association. In 2003, the association had begun to present “memorial sheets” with the biographies of murdered Jewish citizens in a display case at the Michelsberg.

Form of collective memory sought: The architectural competition

The various initiatives to establish a memorial on the Michelsberg — promoted especially by then city council president Angelika Thiels (1941 — 2009) — finally culminated in June 2005 in a resolution of the Wiesbaden city council to invite tenders for a competition of urban planning ideas “for the commemoration by name of the Wiesbaden Jews murdered by the Nazi regime” for the area of the former synagogue. The task of the invited architectural firms was to submit proposals for a redesign of the area around the former synagogue. The traffic function of the busy Coulinstrasse, which today cuts through the former site of the old synagogue, was to be maintained. The landscape architect Barbara Willecke from Berlin and her firm “planung freiraum” emerged as the winner of this architectural competition. Her design for the construction of the memorial, which was completed in 2011, was to be realized.

There were still a number of planning issues to be resolved, such as in particular the structural anchoring of the seven-meter-high reinforced concrete walls on the slope facing the Schulberg and the use of a resistant natural stone material in the area of the Coulinstrasse roadway. Construction work was finally able to begin in April 2010. The ceremonial laying of the foundation stone took place on May 21, 2010. On January 27, 2011, the national day of remembrance for the victims of the Nazi regime, the completed memorial was ceremoniously handed over to the Wiesbaden public.

With memorial area and name ribbon: The building in its details

The name ribbon naming the Jewish victims of the Holocaust from Wiesbaden represents the central component of the memorial. Other main elements are the wall panels that show the overall space of the memorial in the city and the marking of the ground plan and base of the destroyed synagogue. The western wall section is divided by a glass pane about 80 centimeters wide, engraved with the reconstructed interior of the synagogue, a work by Wiesbaden artist Nabo Gaß based on a design by Heinrich Lessing.

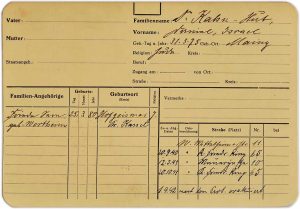

On the inside of the wall panels, at eye level, a ribbon about 1.20 meters high is embedded, bearing the names of the 1507 Jewish victims known until 2011, arranged in alphabetical order by family name. The name of each victim is mentioned on its own natural stone slab with first name, family name, maiden name in the case of married women, year of birth and death, and place of death.

The letters are made with a relief of about five millimeters, so that they can be “grasped” haptically. The five-centimeter-high and 50 to 120-centimeter-long natural stone slabs made of Vietnamese basalt are similar in color and material to those of the wall panels, but differ in their finer surface texture. Blank stones are added to enable the integration of additional names that may be researched later. The ribbon is recessed into the wall. “Stones of remembrance” can be placed on the edge of the recess thus created. As darkness falls, the name band is illuminated.

On the outer lines of the synagogue’s base, seven-meter-high wall panels mark the “empty space” and the location of the destroyed synagogue over a total length of 62 meters. The narrow, masonry natural stone bands are made of Armenian basalt lava.

The entire area of the memorial site is laid out in gray slabs of Chinese basalt. In order to perceive the place as a whole unit, the material of the pavement is color-matched to the wall panels. On the floor of the memorial space as well as on the roadway, the footprint of the synagogue is reproduced. For this purpose, a stone surface contrasting with the surrounding pavement is used. The upper edge of the base of the former synagogue is reproduced on the wall panels by a protruding layer of natural stone. This marking gives an impression of the size of the former synagogue and at the same time rhythmizes the wall surfaces.

The new urban space: counterpoint to the lack of history

The open interior space of the memorial is functionally divided into the accessible memorial space in the incised slope and the adjacent area with the roadway of the Coulinstaße crossing the complex.

The square on the Michelsberg forms the counterpart to the memorial site and blends into the adjacent pedestrian zone. Here, an information board with an integrated touchscreen monitor provides information about the memorial and the former synagogue. Visitors can also access the “memorial sheets” of the Active Museum of German-Jewish History there, which provide information about the fate of individual Jewish victims of Wiesbaden.

Even if the synagogue on the Michelsberg was not rebuilt, the city of Wiesbaden, by realizing the concept of the memorial, has set a counterpoint to the facelessness of history in which the high bridge, demolished years ago, used to cut through this part of the city.